They say, “You never forget your first,” but in my case, my first Final Fantasy was actually VIII. Don’t get me wrong, I’ll always be nostalgic for that rocking soundtrack that worms itself into your brain and addicting Triple Triad card collecting minigame that was necessary for the meta-game, but the title overall never stuck with me the same way that others of my childhood did. Perhaps it was the convoluted love story that never resonated with me, or the equal parts simple-yet-complex Junctioning system, but I found myself returning more often to other entries in the franchise. Ultimately, however, it would be the next game in the series, Final Fantasy IX, that not only has stuck with me the longest, but has also refused to ever let me go.

What starts off as a lighthearted fantasy romp soon descends into an existentialist exploration on what it means to truly be alive. Our protagonist, Zidane, is a member of a theater troupe/roaming gang of thieves attempting to kidnap the heiress to the Kingdom of Alexandria, only to find out that Princess Garnet actually desires to run away. She suspects her mother, the queen, is being manipulated into becoming more aggressive and war-hungry and endeavors to bring her back from such a state. Of course, nothing ever goes as planned, and the ever-growing party must work to find the mastermind behind the conspiracy and save their planet (and all others) from total destruction. It’s your typical JRPG plotline, but where it comes alive is in the characters and how they respond to the threat of their world coming apart.

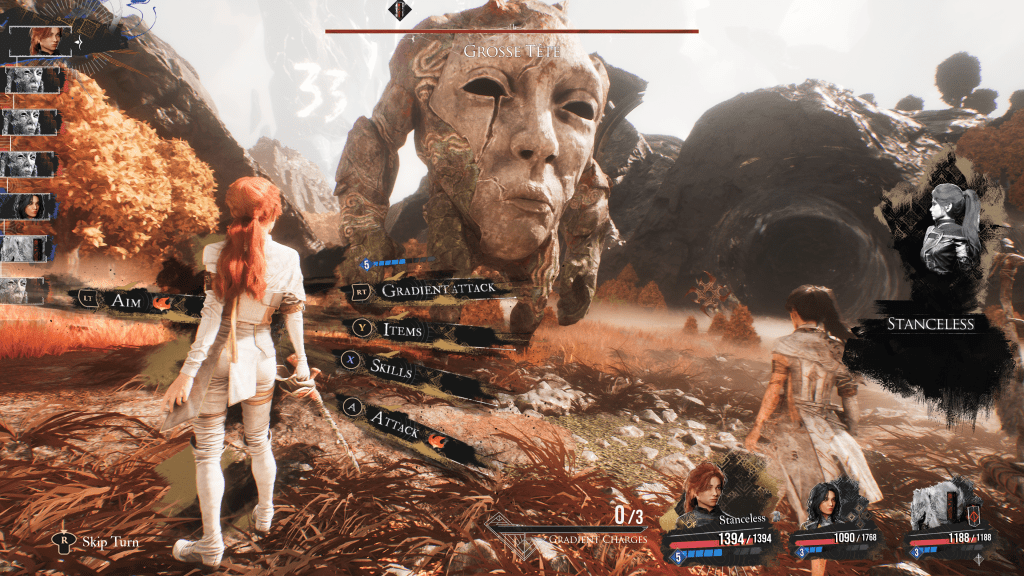

As a game itself, Final Fantasy IX is a culmination of everything the franchise had built and established at that point in time. The final entry on the PlayStation, developers SquareSoft (now Square-Enix) wanted it to be the most jam-packed title in the series to date. The iconic and familiar tropes of the series all return, from the Active Time Battle mechanic to the numerous minigames, and none of it feels tacked on. (Well, you could argue that the card collecting minigame Tetra Master doesn’t have much purpose or utility beyond affecting your Treasure Hunter score, which is only used in a late-game sidequest, but it’s still stimulating enough to include.) Other minigames like Chocobo Hot and Cold, while time-consuming, offer some of the best items in the game and can even lead you to hidden locales and face against secret enemies. You can easily spend hours on these side activities, distracting yourself from the main mission, and yet it won’t feel like a waste simply because of the fun you’re having.

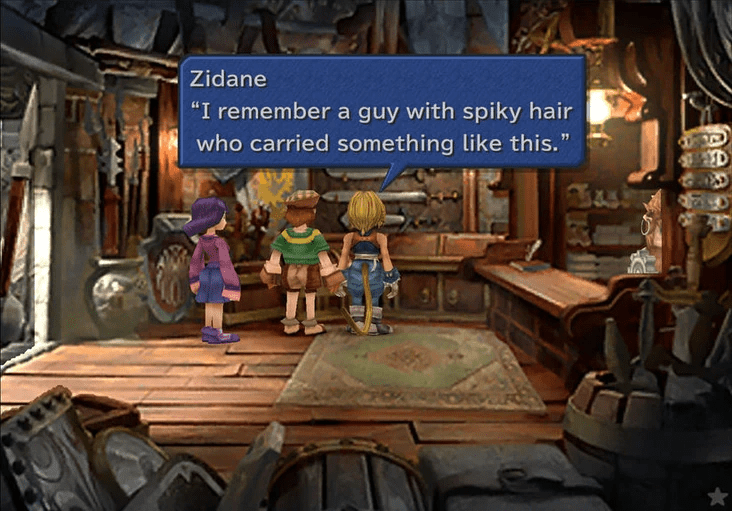

Part of the fun comes from the presentation of the game and its world. As stated before, this was to be the biggest and best Final Fantasy yet and a celebration of the series as a whole. Thus, there are more references, easter eggs, and cameos than can fit in Fat Chocobo’s inventory. Some are on the nose, like an antagonist named Garland or Trance states, but others are more subtle, like the theme to Pandemonium being a slowed-down remix of its II counterpart or the chocobo Bobby Corwen being a reference V‘s Boko. Even other Square games like Chrono Trigger are called upon, and that’s not to mention all of the Shakespearean allusions that make a literary nerd like me go ga-ga.

I just can’t review a classic Final Fantasy game without talking about the soundtrack. This would be the last game in the series entirely composed by a man I believe is foundational to the success of the franchise, Nobuo Uematsu. Self-taught and influenced by progressive and classic rock, Uematsu has helped create some of the most iconic moments across the entire games. Many players will cite the symphonic brilliance of Dancing Mad and One-Winged Angel as some of the best songs in any video game period, and likewise, he pulls out all the stops for FF9. The Darkness of Eternity and A Place to Call Home have found their way into my brain and embedded themselves into my sulci. Every moment, from the epic to the mundane, has Uematsu to thank for establishing the tone and filling you with a sense of wonder.

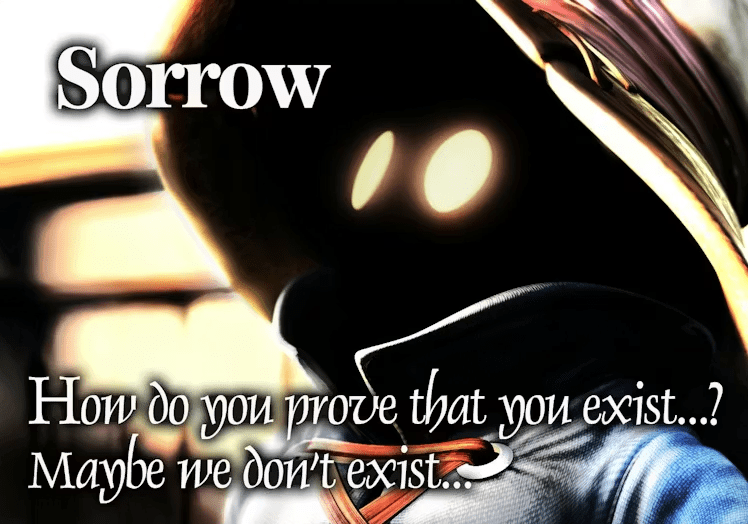

Final Fantasy IX is a tale of finding meaning in a meaningless world. All of the characters are searching for something, whether or not they realize it from the get-go. For someone like Freya, it’s trying to find both her missing lover and her own confidence as a warrior; or for Amarant, it’s the quest to overcome the biggest challenge he can find, to discover what true strength is. Others may not be so obvious, like Quina, who has already found their own life pursuit in the absurd. This wide-ranging and wild cast must confront how to find define their existence in a world that balks at such a concept, and this can be perfectly encapsulated within the development of one character in particular: Vivi.

The black mage of the group quickly learns his true origin: as a prototype for a fighting force meant to conquer the world and destroy as much as possible. His function is already predefined as a weapon of war, but growing up and living among the people of Gaia changes Vivi and helps him to discover that it is up to only himself to find what answers life has to offer. Many fear him as a destroyer and a killer, built only to cause destruction, but he rejects this determination and impels himself to protect the ones he loves, even knowing his own death is on the horizon. Life may have had a different purpose in mind for him, but he stands up in the face of the reason for is creation and instead finds one that matters to him. This is the thematic underpinning that reverberates throughout the entirety of the story.

A core tenet of existential philosophy is to define oneself through free will and choice. Life is considered to be absurd; that is to say, it is devoid of greater meaning, lacks significance, and is reduced to nothingness in the end. It is up to each individual to make a choice: do you succumb to that meaninglessness and accept despair, or do you resist against that emptiness and, instead, search for your own meaning? One of my favorite essays is “The Myth of Sisyphus,” and those of you who already know me will know where I’m heading with this. Albert Camus posits that the human condition is one of suffering, that existence is irrational, and that death overtakes all ultimately. So, then, what should one do in the face of such a lack of hope? To Camus, it means to pick yourself up, to continue climbing that mountain, and to find resolve in those rare moments of lucidity. We have to find pleasure in the present, to enjoy what is in front of us, and to live for the moments that bring us relief from the absurd.

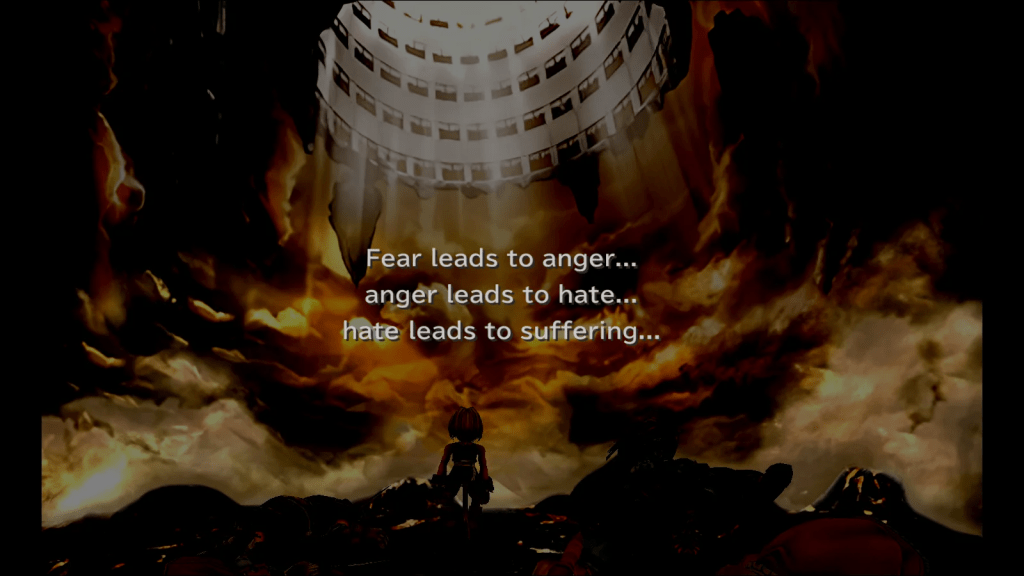

This is encapsulated in the interaction between Zidane and the controversial final boss, Necron. After learning he is fated to die, the primary antagonist, Kuja, decides to destroy all of reality along with himself, and through such an act, summons a being of anti-existence, a creature who sees life as only an extension of suffering. Kuja’s existential crisis is what ultimately spurs Necron into being, claiming that life is a cycle of woe that can only be broken via the eliminating all life to a state of nothingness. In its mind, the only way to prevent suffering is to ensure that nothing can exist which will suffer.

Of course, the party rejects such a theory. Each of them has learned to find their own purpose in existence, not the one assigned to them. Life may involve suffering, but it also involves joy, friendship, and love, things that ultimately make our transient and temporary experiences worthwhile, and it’s exactly that resistance against the absurd which enables them to overcome the embodiment of death. Whereas Kuja takes ends up taking a selfish and nihilistic view to his life, to the point of attempting to destroy all of existence with him, the party finds meaning in the bonds they have with each other and choose to lift one another up. It is literally what gives them the strength to overcome the anguish of defeat flooding over them upon Necron’s actualization, and in the end, a dying Kuja learns what it means to live in his final moments. Purpose can take many forms, whether a passionate pursuit, dedication to self-betterment, or in the relationships you form, but no matter the source, they are what make life worth living. In the end, the heroes prevail and each goes on to live a life which is fulfilling to them.

Maybe that’s why I keep finding myself returning to this game every few years, sometimes even multiple times in the same year. Sure, nostalgia has a big role to play in that, but so does the majesty and mystery of the world, the purpose each character has to find in such a world, and the challenge of overcoming insurmountable odds in finding such a purpose. As I sit down to write this, I find myself particularly drawn to Vivi’s words in the epilogue: “To keep doing what you set your heart on… It’s a very hard thing to do. […] But we need to figure out the answer for ourselves…” True meaning still seems to escape me from time to time, but knowing that I do not struggle alone and that I can help others to find their own meaning gives me the strength to persist.