I probably started playing the God of War games when I was way too young. When the first entry in the series was released on March 22 nineteen years ago, I was only 11 years old. By that point, I had already been exposed to enough graphic media that one more piece couldn’t hurt. Apart from being blown away by the behemoth brutality on display, this was the period in my life when I was obsessed with other culture’s mythologies. Greek, Egyptian, Norse, it didn’t matter. The combination of a rich and (at the time) unique story with difficult combat and puzzle-solving, plus all of the creative ways to mutilate enemies, made me instantly a fan. It had been quite a long time since I had played any of the older games, and after finishing the Valhalla story DLC in God of War: Ragnarök, essentially wrapping up Kratos’ arc, I felt like it was time that I experienced the whole series, back to front, including the entries I had missed when I was younger.

So, after digging an old PS3 out from my closet, purchasing a couple games missing from my collection, and figuring out how to get an old Java Platform Micro Edition emulator running properly, I was ready to begin.

Two quick caveats before I begin: firstly, all of these games have been beaten on Hard difficulty. Easy and Normal are good for speeding through, but Hard gives enough of a challenge without wanting to throw the controller across the room (most of the time, at least). Secondly, I did not go out of my way to find all of the canon media, like the comics or novelizations. I only wanted to play the actual games themselves.

Oh, and obviously, there will be spoilers for the entire series.

God of War: Ascension (2013)

This was only the first of three games in the entire series I had never played the first time around, so it was fascinating to play the game that was considered to be the cause of the “God of War fatigue” of the early 2010s.

By the time Ascension came out, people were tired of the formulaic gameplay and uninformative narrative that the game was considered to contain. The antagonists, the Furies, don’t feel quite as strong villains as future enemies do. The primary conflict can be summarized as “Furies help Ares and have a son who helps you, kill them or they’ll haunt you,” greatly lowering the stakes. The entire story itself, told in a confusing non-linear fashion, centers on Kratos’ memory having been lost as a result of betraying his blood oath to the god of war. Upon defeating the avatars of vindication, the memories of Kratos killing his own family return to him. If this was your first entry in the series, that would come as a surprise; however, veteran players already know this at this point, and Ascension‘s narrative does little to add to that struggle.

As with every other game across the entire franchise, the combat is fluid and dynamic, incentivizing the player to try out different techniques to take on the hordes of enemies. This time, instead of numerous special weapons and magic, Kratos wields the elemental powers of the Olympians, which grants him his special abilities, along with two combat utility items. Because of this system, magic isn’t immediately available for some of the elements, requiring you to become proficient at dodging and parrying. The Rage meter has also been completely changed, granting you a single powerful attack as opposed to temporary super strength.

All of these combat changes are a result of rebalancing due to the addition of a multiplayer mode. Players take on the role of a warrior aligned with one of four Olympians, Ares, Zeus, Poseidon, or Hades; each patron deity provides different powers and combat roles. Whether cooperating with or competing against other players, the goal is almost always the same: kill, kill, kill; making the mode seem somewhat repetitive. Each of the arena locations, however, provide unique mechanics, like a cyclops that can attack players, helping each backdrop feel more than just a change of scenery.

The boss fights, as with every entry in the series, feel sufficiently epic and massive, and enemy executions are particularly savage this time around, especially with the elephantine Juggernauts or the serpentine Gorgons (who add fuel to the fire of the great “sniddies” debate of 2021). Ultimately, had this game been released before God of War III, it might have done much better. However, the “paint-by-numbers” nature of it makes it, perhaps, the worst in the series. Don’t get me wrong, however; “worst” is a stretch. This is still a really good game worth the time to play.

God of War: Chains of Olympus (2008)

Chains of Olympus was the first of two PSP games in the franchise to be developed. I played it back-and-front as a teen, trying to experience everything it had to offer.

The inclusion of this game does throw a wrench into the overall narrative of the series. Following a semi-predictable story in which Kratos has to rescue Greece from the clutches of Morpheus and Atlas, the game ends with our hero killing Persephone, Queen of the Underworld. It should be more greatly emphasized that Kratos has now officially killed a god, as well as the primordial Furies, by this point. It’s supposed to be a big deal when he uses the power in Pandora’s Box to kill Ares in the next game because a mortal is killing a god, but “oh well, he’s done this before, and just with his normal weapons.” This is never acknowledged across the rest of the games, and yes, I know this game was released after the original, but the retcon just creates more confusion.

For being a handheld game, it delivered as much of an experience as any of the PS2 games. The graphics actually held up to console standards, which is extremely impressive for a handheld device. Each of Kratos’ new abilities feel unique and powerful. I especially liked the Fist of Zeus and am sad it only appears in the last third of the game. Surprisingly, the combat could be frustratingly difficult at times, and when coupled with unforgiving checkpoints and unskippable cutscenes, repeated boss fights or combat encounters become increasingly exasperating. What comes to mind in particular is the parrying. I don’t know why, but I had more trouble reflecting attacks in this game than in any of the others; I could never get the timing right on it.

That is not to say this is a long game. In fact, I have been able to beat it in a single sitting. There aren’t any puzzles or platforming sequences for players to get stuck on. You simply move from one area to the next, defeating enemies along the way. Overall, it’s just a portable God of War game. I wouldn’t consider it to be anything special other than the fact that you can carry it with you in your pocket. It’s also notably deflating that, while saving Greece should be a good bargaining chip for Kratos against the gods, he ends up unconscious and all his goodies taken away, ultimately caught with his pants down and nothing to show for it. No wonder he has such ill will toward them.

God of War (2005)

The one that started it all, the first game in the series, the rise of the new god of war.

This is the explanation of how Kratos, in service to the gods, gained the power to slay Ares and ascend to his throne. As he explores the labyrinthine Temple of Pandora, more of his story is revealed; his beginnings as a Spartan general, his tension with his wife and child, his pledge of loyalty to Ares to prevent being killed by the barbarian king Alrik, his accidental killing of his family, and his curse to forever be the Ghost of Sparta. Everything that the future games would build upon are established here, the foundations to the altar of violence.

If there’s one word that can summarize this game, it would be “gratuitous.” There’s blood and nudity galore, an almost excessive amount by today’s standards. The combat feels equally epic as a result. It’s very easy to feel powerful when you’re literally tearing legionnaires in half with your bare hands. Just imagine what it must feel like to defeat a giant armored undead minotaur by staking it in the heart with a massive ballista. On the other hand, this is definitely the hardest game in the entire series. Enemies really soak up the damage and Kratos, for being a demigod, can get knocked over by a slightly errant breeze. One of the hardest segments of the game, as a result, are the rope-pulling segments, where legionnaires can very quickly surround you and pull you off, while you can only slowly pick them apart. The platforming can be equally unforgiving, as demonstrated by a certain, infamously difficult area within the Temple of Pandora: the Blades of Hades. Balance beams plus spinning blades equals not a fun time; I stopped counting after 17 deaths.

In the end, it’s indescribably satisfying to defeat Ares because it is the absolute hardest boss fight in that generation of console gaming. There are three phases of fighting him, each with unique movesets or constraints: one where you have all of your abilities available, one where you have to protect your wife and daughter from ever-spawning manifestations of Kratos’ wrath, and one where you duel with longswords. He can easily take you out with a single combo if you aren’t careful. It took me hours to finally bring him down, and I still have unpleasant dreams about the second phase.

I find it strange that Hades would assist Kratos and grant him magic powers, fresh after he had just murdered the King of the Underworld’s queen. Likewise, if the Temple of Pandora was 1,000 years old, how is there a statue of Atlas carrying the world on his shoulders, when Kratos only made that happen sometime within the last 10 years? Did Pathos Verdes know something the Fates had told him? I’m going to try to avoid nitpicking retcons, but it’s hard when so much of the base story begins to fall apart because of the newer games.

All in all, this is an excellent start for the rest of the franchise. Everything we have come to know, expect, and love about the future games originated from here, setting the high standard for which every other entry would attempt to surpass.

God of War: Ghost of Sparta (2010)

This was my first time playing Ghost of Sparta, for whatever reason being unable to purchase it at the time.

As the newest Olympian, Kratos uses his newfound power and influence to lead a force to the (not-yet-sunken) city of Atlantis, attempting to find the source of strange visions which plague him. What he does not yet realize is that he will rediscover the missing memories of his past, including a brother who was taken away by the gods and is chained within the Domain of Death, ruled by the primeval Thanatos. Upon learning this, however, Kratos makes it his priority to save Deimos and hold onto the last vestiges of his mortality.

Upon seeing the slaughter of Ares by the hands of the once-mortal Kratos, did the rest of the Olympians not ask, “Why are we still screwing with this guy?” Yes, it is later revealed exactly why Zeus and the rest of the higher gods turn on the newly-crowned god of war, but still, have they just not seen what this mortal is capable of? No wonder he’s so antagonistic toward them by the start of God of War II, and why the Olympians become paranoid enough to try and kill him. It also explains why Poseidon is so furious toward Kratos at the start of God of War III. Instead of retconning story elements and creating plot holes, this game is attempting to weave the overarching narrative together. Still, I like how everything that goes wrong in Greek mythology is Kratos’ fault. Atlantis’ destruction? Kratos. Atlas holding up the world? Kratos. Apollo stubbing his toe? Kratos.

Even though I was using the upscaled PS3 version, the visuals were still impressive. If that is close to how they appeared on the original PSP version, the quality of the graphics would have been equal to games on home consoles. Kratos’ varied facial expressions and rain slicking on characters’ bodies are extremely remarkable on a portable system. In these versions of the game, only really the textures and resolution are updated, otherwise the work would have to be put into remaking and rigging all of the models, which is absolutely ludicrous to consider. Watching captured footage of the PSP version only solidifies my point: these graphics are excellent.

What is less impressive, however, is the inflated level of challenge. There were numerous times where I found myself stunlocked by an enemy’s combo, unable to roll or block, only to end up completely obliterated when I started with a full health bar. There were certain encounters that required multiple replays in order for me to learn the monsters’ attack patterns, dodge preemptively to avoid taking even slight damage, and combo-break the enemies whenever I could. If the game is going to be cheap, it’s only fair that I use the game’s systems to be cheap myself. Ultimately, it was not that hard, but it just felt more tedious to get past certain challenges.

Other elements just left me unsatisfied, like the new Fire Meter mechanic, which would appear again in God of War III. Hold down a button during your attacks to temporarily boost their power, and letting go of the button allows the meter to quickly refresh. However, I felt like it didn’t add much complexity to the combat, just something additional I had to look out for. And it might just be me, but the red orb chests were in extremely predictable places this time around. Maybe it’s because I’ve studied game development or maybe it’s because I’ve played these kinds of games many times before, but I never found the “secrets” to be all that secret.

In the end, I thoroughly enjoyed this entry. Callbacks, like the Callisto boss fight, and foreshadowing to future games, like with the sinking of Atlantis, make Ghost of Sparta an excellent tie-in.

God of War: Betrayal (2007)

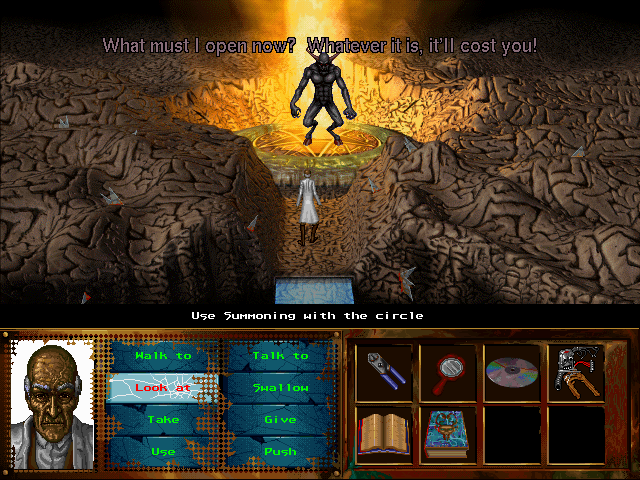

The last of the God of War games I had never played before, this one was a little difficult to acquire. Primarily compatible with old Nokia and Sony Ericsson cellphones, Betrayal had never been released for any other platform, hence my necessity to find a Java ME emulator and a working JAR capture.

As Kratos and his army kill their way across Greece, an unknown assassin attacks and kills the creature Argos, framing Kratos in an attempt to turn the gods against him. He chases this assassin across Greece, and eventually, Ceryx, son of Hermes, attempts to stop Kratos and warn him of the consequences of his rampage. However, the god of war kills Ceryx, the assassin escapes, and the Olympians are further distressed by Kratos’ actions, hastening their eventual retaliation.

It’s an old mobile action-platforming game; there’s not a whole lot more to say. The controls were finicky, with Kratos sliding around the screen, perhaps a symptom of the emulator, but also perhaps poorly-designed. Some of the design choices were puzzling, in particular allowing the minotaur execution minigame to be canceled out by the environment. If part of the attack is blocked by the ceiling, the attack animation simply stops, leaving the player literally stunned and unable to move. The actions available to the player are extremely constrained, limited to back-and-forth movement, jumping, a basic attack, magic spells, and a sub-weapon, but you’ll never need to use most of these. Your regular blades will often do the trick the vast majority of the time; I was able to beat the entire game without upgrading anything other than the Blades of Athena and mashing the attack button. The story is ultimately insignificant, with the identity of the assassin never being revealed and the Olympians already having animosity toward Kratos. The music, which is almost always a core staple of the franchise, is negligible here, severely lacking in this important regard.

I don’t want it to seem like I have nothing positive to say about this game, however. The sprite work is very good for 2007, with each character, enemy, and background element standing out. I could see myself having used these sprites in old, now-long lost comics I once made. I was also appreciative of the forgiving checkpoints, the game seeming to auto-save every few steps I took. This was helpful, as the game itself isn’t particularly difficult but I still found myself dying a lot anyway, primarily because of the platforming and being stunlocked during the minotaur execution.

It only took me around an hour to beat this game. There really isn’t anything else to write other than that. I’m glad I played it, but the juice was not worth the squeeze.

God of War II (2007)

If there’s anything that sums up my experience with God of War II, it’s this little factoid: I had been playing and gotten to about halfway-through when I realized I hadn’t taken a single note yet. I was just having too much fun playing the game. God of War II was always my favorite of the original games, and I think it still is.

At last, Kratos’ crusade through Greece has gone too far, and Zeus traps and kills the god of war after an epic battle in Rhodes. However, he is rescued from death by the titan Gaia, who aids Kratos in finding the Sisters of Fate to change his past and defeat Zeus when he is vulnerable. While killing his way across the Island of Creation, he fights mythic heroes like Theseus and Perseus, monstrous creatures like the Gorgon Euryale and the undead Barbarian King, and eventually encounters the Fates themselves: Atropos, Lakhesis, and Clotho. When they refuse to change destiny, the god of war does what he does best, returns to the past, and nearly kills Zeus, but because of Athena’s interference, she is instead killed, revealing to Kratos that Zeus is his father. The game ends with Kratos returning to the distant past, to the Titanomachy, recruiting the titans to the present in order to lay siege to Olympus. I have no time to get into the plot holes caused by this game with the inclusion of time travel. Suffice to say, as with all time travel stories, you have to just either accept it or else let the premise completely fall apart.

The balance of challenging combat and elaborate puzzles is at its peak in this game. I never felt stuck for significantly long, even on the hardest difficulty. That’s not to say I prefer easy games, but I enjoy them more when the challenge is fair. As an example, the boss fights in this game are nowhere as frustrating as in the original. Euryale and Theseus are supposed to be the two hardest enemies, and yet, I managed to beat them in roughly five attempts each. Just to compare, it took me twice as long to beat the Cerberus Breeder in the first game. Likewise, as hard as the fight with Zeus was, I still was able to take him down much more quickly than Ares, an encounter that I had to spread out over days to overcome.

Maybe it’s just me, but I never loved using the sub-weapons in these games. This time around, we have the Barbarian Hammer and the Spear of Destiny. Reading about them online indicates that they’re both effective weapons once you invest experience into them, but after putting so many into the Blades, it feels like a waste to use the other weapons. I was also not as big a fan of the magic this time around. I don’t know why, but they did not feel as iconic nor as powerful as the abilities from the first entry. However, upon beating the game and unlocking Bonus Play, you are able to use the Blade of Olympus, by far the best weapon and one of the most recognizable across the series. There are a number of emblematic designs that originate from this game, in particular, Kratos wearing the Golden Fleece or in his God Armor. One neat inclusion that doesn’t necessarily affect anything, and yet I found myself enjoying, was the addition of the Status Screen in the pause menu, which tracks how many enemies you’ve killed, times you’ve died, times you’ve saved, and other statistics. I always found those to be a neat way of tracking progress.

Even though this game was developed before prequel entries like Chains of Olympus, it’s really great to see them setting up elements they would explain later, like Atlas blaming Kratos for being forced to carry the world on his shoulders. It’s nice to see them setting things up that they would explore later, emphasizing how impactful and important this game is to the rest of the franchise.

The end of an era, the culmination of years of bloodshed, the desolation of the gods. This is what is promised to players within God of War III, and that is exactly what we get.

Betrayed by the titans and denied his revenge, Kratos has to climb from the Depths of Tartarus to the very peak of Olympus, dismembering deities as he makes his way up the mountain. It is during this ascent that he encounters the homunculus Pandora, a creation by the god Hephaestus, a girl trapped by Zeus as the key to reopening her eponymous box. Only by plumbing the hidden caverns of the gods’ home will Kratos discover not only the means to defeat the Olympians, but also reclaim the missing remnants of his humanity. Despite this game focusing on the twilight of Olympus, it was the most thematically hopeful game yet, a sentiment I thought felt didn’t belong at the time. To this day, I’m still not sure whether its current execution fits.

Both the PS3 and PS4 versions of this game look gorgeous, from the detailed environments to the goopy and jam-like blood, to the unique character models of humans and creatures you encounter, and beyond. Everything has to look and feel just right for a gratifying conclusion. Because you’re fighting the most legendary of beasts and gods at this point, it’s only fair that the boss battles feel sufficiently big, and God of War III excels at that. Beginning with the Poseidon fight as you and Gaia scale the mountain throws you right into the action, something for which the series has come to be known. In particular, however, the Chronos fight stands out as memorable. You climb across his body, slaying enemies on his arms as you systematically tear off fingernails and rip open his torso. Brutal, and a perfect example of the methods of death available to Kratos.

Across the entire game, though, the combat depth has been adjusted. The combat feels “weighty;” the slight delay in your dodge roll, the flowing through weapon combos, the grappling of each enemy; every action has heft to it, reciprocating a sense of satisfaction as you make your way from group to group. This is somewhat reflected in the new weapons available to Kratos. Instead of unique sub-weapons, this time, three out of the four you receive are essentially swords on chains: the default Blades of Exile, the Claws of Hades, and the Nemesis Whip. Only the Nemean Cestus are different, as weaponized gauntlets. The combos and magic abilities available to you change depending on the weapon in use, but for the most part, all of them feel like extensions of the Blades.

The part that always sat uneasy with me was the idea of hope saving the day. The evils which corrupted the Olympians was unleashed when Kratos opened Pandora’s Box in his quest to defeat Ares, but also released was the power of hope, which has been within Kratos all this time, giving him the strength to persevere and annihilate the gods. It was like the kind of ending you’d get in a cheesy anime or a Saturday morning cartoon. It always felt too sentimental for me, and God of War wasn’t necessarily about sentiment. Little did I know how the series would not only eventually make this work, but create an even-more thrilling and rewarding experience through its use of sentimentality.

Nevertheless, I was immensely surprised by the post-credits scene, where, after Kratos stabbed himself to release hope to the ruined Greece, we see a trail of blood leading to the torrential seas. This was not the end of God of War, even if it was the end of the Greek saga.

God of War: A Call from the Wilds (2018)

I’m lucky that friends of mine had invited me to attend PlayStation Experience 2017 with them, because had I not, I probably would never have been able to try this piece of lost media.

Once accessible through Facebook’s Messenger service, this defunct game now exists only in YouTube videos and articles such as this one. While it’s odd to think of this game as only appearing on a social media app, it worked well as a text parser, a modern kind of text-based adventure game, in the vein of Zork or AI Dungeon, although the game came with collectible artwork to help set the mood and get players prepared for the new entry. A prequel to the then-upcoming newest entry in the franchise, players took control of a boy living in the woods with his mother as he assists her with various tasks, being captured by vicious undead Draugr, and eventually taking control of an ashen-skinned man with a red tattoo across his head and chest. While I did not know it at the time, this was the first look we had at Kratos and new family, his wife, Faye, and son, Atreus, after he settles down in the Norse realms. How he got there is yet unknown to us, but it was comforting to see that the former god of war had managed to leave his need for vengeance behind him in some regard.

Atreus, long before learning about his godly heritage and awakening to his powers, can hear and feel the thoughts and emotions of animals around him as he explores the area around his home. A lot of the narration during his segment focuses on how empathetic he is and the power of that empathy already manifesting. As Kratos, however, the only real tasks required of you are to absolutely destroy the Draugr attacking Atreus, and then to either scold, ignore, or advise his son. We already get a glimpse at the upcoming dynamic that would be the base upon which the newest game would build, the tension Kratos has with his child, hoping to lead him down a different path than the one he experienced in life.

That’s the primary purpose of this game: to act as a small narrative bridge between the game’s two sagas. We get a sense of what the major characters are like and the kinds of struggles they will face, as well as foreshadowing future events, such as when “You look at the strange mark on the tree. A sense of comfort washes over you, but you aren’t sure what the marking means.”

God of War (2018)

Solemnly, Kratos cuts down a tree marked with a yellow handprint, and with the help of his son, Atreus, they bring it back home to complete the funeral pyre for the now-deceased Faye, promising to carry her ashes to the highest peak in all the realms. This stark, emotional opening, with minimal dialogue and presented mostly through facial expressions, sets the tone perfectly for the new direction down which God of War has gone.

Everything that was familiar and comfortable to past players was left behind in Greece. It was very strange seeing God of War with Dark Souls-like combat, an RPG leveling system, open-world exploration, and a narrative rooted in forgiveness and redemption, but it all works. The combat requires a whole new level of strategy, having you consider your actions and counter the enemies’ powerful attacks, as opposed to blitzing in with spinning weapons. The Leviathan Axe is one of my favorite weapons in the series, between the sheer power behind each attack and the ability to throw and recall it, like Thor’s mystic hammer Mjolnir. Exploration never felt like it dragged on, as hidden chambers and various side quests could only be unlocked by advancing the story further. Originally a solo adventurer, Kratos is now joined by a pair of Dwarven brother blacksmiths, Brok and Sindri, and the reanimated head of the smartest man alive, Mimir, all of whom are laugh-out-loud funny at times, even if they get on Kratos’ nerves. All of these new inclusions could have felt wildly out of place if implemented improperly, but Santa Monica Studio took care to craft an unforgettable experience.

Kratos has more than mellowed out by this point, but we can see him making many of the same mistakes that he is attempting to avoid, telling Atreus, “We do what we please, boy. No excuses,” and, “Close your heart to their suffering.” This only adds fuel to the fire once Atreus begins going through his moody and angsty phase, and absolutely reinforces why I do not want children of my own. As you progress and their understanding toward one another increases, after completing combat sequences, Kratos will go from giving Atreus criticism eventually to praise. These small moments of interaction between father and son help to further establish the strong character arcs that act as main narrative throughlines across the game’s story.

By far, my favorite portion of the game is when Atreus falls sick and, needing to explore Hel in search of ingredients for medicine, Kratos must reclaim the Blades of Chaos, hidden beneath the floor in his home. Everything, from Athena’s appearance and taunts to the subtle red vignette signifying Kratos’ inner rage, is absolutely sublime, culminating in the moment when Kratos admits he is and will always be a monster, “But I am your monster no longer.” As a fan of the entire franchise, this feels like the satisfying conclusion to the Greek saga that I was missing.

God of War: Ragnarök (2022)

To summarize my feelings about God of War: Ragnarök, everything about this game is bigger and better than its predecessor. The combat has more complexity, there’s more variety in the optional content, and the narrative depth is oceanic. However, I still prefer 2018’s God of War because of my emotional connections to the references to older games in the series. Essentially, this is brilliant, but I like this. That’s not to say I didn’t thoroughly love Ragnarök. On the contrary, it was probably my Game of the Year for 2022.

Upon learning that his son, Baldur, was killed by Kratos, the Allfather Odin surprisingly agrees to leave Kratos alone so long as Atreus stop searching for the lost god of war, Týr. After dueling with Thor and fleeing their home, the pair actually rescue Týr from another realm, and are slowly dragged into the building conflict between Odin and all others that will lead to the apocalyptic battle of Ragnarök, the effects of which will be felt across all of the Nine Realms. In an attempt to subvert such destruction and claim a mysterious primordial power that could consolidate his rule permanently, Odin uses trickery and deceit to drive a wedge between the father and son, but fails, and the two wage war against Asgard, this time fighting to protect instead of to destroy. If 2018’s God of War is a story about mourning and recovering, Ragnarök is a story about survival and perseverance.

Odin is an amazing contrasting antagonist to everyone else across the series. Ares, Zeus, the Furies, and the rest are all bloodthirsty and lacking nuance as far as their villainy is concerned. Odin, however, is conniving, intelligent, and sneaky. His charisma almost makes you want to believe what he’s doing is ultimately the right thing, and then he goes and commits some atrocity that reminds you he is only selfishly looking out for himself. It’s a refreshing change to the straightforward villains of the previous games. This alone helps to set the tone that conventions will be broken all the way around, which Ragnarök does well. You are constantly on your toes, waiting for something else to happen, something new to be introduced. It’s not like constantly being on edge, anticipating some new enemy to come dropping out of the sky; it’s more of a sense of wonder about where else this game leads.

The downloadable epilogue Valhalla is a perfect addition to the game and an excellent excuse to add more playtime. Receiving an anonymous invitation to the land of eternal combat, Kratos fights his way through randomized groups of enemies using an ever-changing set of abilities, all as Kratos explores his past, contemplates his future, and considers whether to take up the mantle of God of War once again. I’m a huge fan of roguelites: shifting layouts that change with each attempt, choices in specific movesets and abilities, a story that only unfolds as you repeatedly defeat a surprising final boss. It requires you to master all of what the game has to offer, not allowing you to be too comfortable in one particular playstyle. Plus, all of the cosmetic options provided allow you to adjust the appearance of Kratos’ armor and weaponry however you’d like.

It is uncertain where God of War will head next. All I know is, whether following Kratos or Atreus, whether in Ancient Egypt or Shinto Japan or wherever else, I’m along for the ride.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24466950/ifrit_vs_garuda_fireball.jpg)