Some games, I’ll pay attention to years before their actual release. I remember when The Last of Us had been announced, and the only discourse surrounding it was how much Ellie looked like Elliot Page. Other games, I’ll hear about for months after release before I finally decide to pick it up. It took listening to not one, but two separate podcasters talking about Balatro before I went in on one of the best indie games of last year. Others still, however, will appear seemingly out of nowhere, a bloom amongst the weeds. It may not have been heralded by any pomp and circumstance, but the ripple it leaves when cast into the ocean of video games can be massive. Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 unexpectedly came into my life while browsing Reddit, and with my feed now being filled by posts about what is being considered one of the greatest games of this generation, I had to sate my curiosity.

Roughly 70 years before the start of the game’s plot, reality was broken apart in an event known as the Fracture. This moment welcomed the Paintress into the world, an immensely powerful being who paints a number on a massive monolith, marking anyone aged above that number to die. Fleet after fleet of Expeditioners, scouts and warriors representing the last vestiges of mankind, embark every year to take down this enemy and free the world, to no avail. You join the latest attempt, Expedition 33, as they set off from the haven of Lumière in order to break the cycle of death and ensure a future for those who come after.

I really don’t want to get more into the narrative if I can avoid it. This is one of those stories that has to be experienced to properly take it all in. Reading a synopsis or hearing a reaction does not do justice to one of the most poignantly written games I’ve played in quite a while. What starts off already as an incredible fantasy epic eventually becomes an exploration of the very meaning of existence, the power to create, and the responsibility of the creator. It also helps that the high-quality writing is complemented by the fantastic voice work performed by the actors. In particular, Charlie Cox, Ben Starr, and Rich Keeble all brought smiles to my face with their roles, bringing the script alive. The complexities of the story become even more entangled by the end, but not to the point of being an unintelligible mess. There is a story the game wants to tell, and without compromising itself, the developers tell that story, making some bold and outright risky decisions that could easily alienate audiences if executed poorly. But by taking those chances and sticking the landing, Sandfall Interactive steps into the spotlight as a developer to watch in the future.

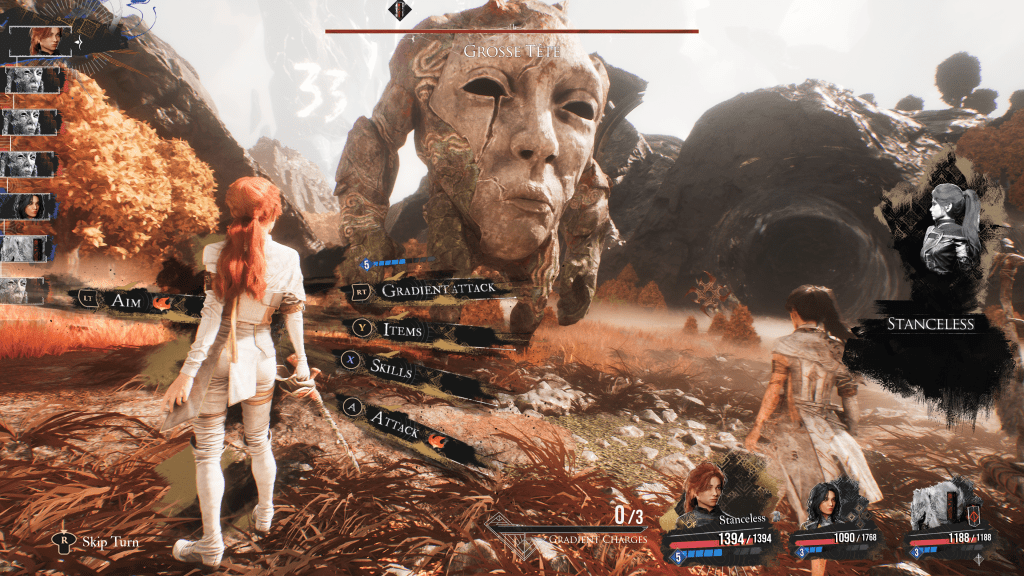

A quick search on Google can show you that, ironically, for decades now, people have been discussing whether turn-based gameplay is actually boring and dying out. The idea seems to be that while it was innovative at the time and helped to get around hardware limitations, it is obsolete in today’s marketplace. Anyone who’s actually paying attention can see turn-based games are maybe even more popular than ever before, with the success of Baldur’s Gate 3 and Persona 5. Clair Obscur’s take on turn-based combat has led to a revitalization of this topic, demonstrating just how alive the mechanic truly is. Along with being able to select whether to use a basic attack, a skill, an item, or other actions during your own turns, players can also attempt to dodge and parry enemy attacks during their turns as well, something I remember first seeing in Paper Mario all the way back in 2000. You’re not just stuck waiting to go again; each move actively keeps you engaged, whether you’re attacking or defending, meaning you’re constantly plugged into the battle. Each character you control also has additional mechanics making them unique in combat, whether building up spells to empower other spells or activating synergistic abilities to increase damage or ability effectiveness. Until you find the right combination of player character moves and passive upgrades, experimenting with the combat system will take a while to build any proficiency in. After nearly 60 hours, I was still struggling with the pacing and timing of certain enemies’ attacks while others I could defeat without taking any damage. It’s challenging, but rarely to the point of frustration. Learning some bosses’ patterns can take some time, but it is incredibly satisfying to land a perfect counterattack after watching all their moves.

Many comparisons are being made between Clair Obscur and Final Fantasy, in part due to the latter’s stranglehold on turn-based RPGs. Although their games have moved away from that direction as of late, the similarities between the two franchises go much deeper than combat format. As mentioned above, Ben Starr appears in the game as a broody, dark-haired sword wielder looking to free those trapped in circumstances beyond their control, very much alike to his starring role in Final Fantasy XVI as Clive Rosfield. Soon after meeting this character, you’ll also be introduced to another whose gimmick is being able to transform into the various enemies you encounter and use their own abilities against them. By taking their feet (de-FEET-ing them, if you will), they can actually use that enemy’s special combat moves on his own turns, like Blue Mages across the Final Fantasy series, including Gau from FF6, Quistis from FF8, and Quina from FF9. The biggest influence Final Fantasy has on Clair Obscur, however, seems to be the combat. Specifically, the turn-based mechanics used in Clair Obscur seems to be directly inspired by Final Fantasy X‘s Conditional Turn-Based battle system. Unlike the traditional Active Time Battle, where each character and enemy have an internal “clock” that determines when a turn can be taken, a turn list can be seen in the corner, displaying who is about to move and who is next in the queue. This turn order can then be manipulated by player or enemy actions; for example, using Rush to increase player agility may allow you to take another turn before the enemy can make their own. I was disappointed when Square Enix moved away from this style of combat, as I actually think it’s the best way to present turn-based battles. This method allows for better strategizing, with players able to plan characters’ moves multiple turns in advance or changing up tactics in an emergency. It’s an underutilized mechanic that refreshes the stagnation of normal turn-based combat, and it’s great to see a modern game embrace it once again.

Persona‘s influence can also be felt on Clair Obscur, particularly in the way the UI is displayed in combat. The game’s own director has praised the Persona games for their stylish presentation, with a dynamic menu and camera angles putting you directly in the battle. Between Final Fantasy, Persona, and Paper Mario, among many others I’m likely forgetting, Clair Obscur is a French love letter to JRPGs (making it a Je RPG) that has been done so masterfully, I legitimately do not see how another game will surpass it this year.

It may surprise you to hear, then, that Clair Obscur is actually Sandfall Interactive‘s first release as a developer. Director Guillaume Broche originally worked on Ghost Recon: Breakpoint and Might and Magic: Heroes VIII before leaving the studio to pursue making the kinds of games he wanted to create. Lead writer Jennifer Svedberg-Yen, was originally hired as a voice actor based on a Reddit post calling for auditions. Even composer Lorien Testard was discovered on SoundCloud, with this being his first game project ever. The odds were very much stacked against them in an industry with higher and higher budget costs, but their focus to deliver a complete, enjoyable, and gratifying game helped them to keep their eyes on their goal.

When talking about budgets in the video game industry, there are generally three kinds of games. Triple-A (AAA) games are the most expensive and funded by the biggest publishers, with access to much more resources and marketing. These are your industry giants, your Grand Theft Autos, your Call of Dutys, your Mario Kart Worlds. On the other side of the spectrum, we have single-A games, but no one ever calls it that, so let’s just refer to them as indie games: independently funded, usually created by a small team or even a single person. The previously-mentioned Balatro would fall under this category, as would Cuphead or Hades. Somewhere in the middle lie double-A (AA) games. These might be made by a bigger indie studio or a large non-indie studio, generally under 100 employees. They get their funding from publishers who don’t own the developer or cannot otherwise dictate how they make the game. As a result, the teams have more creative freedom when making them, but the budget constraints can be a major source of tension for the developer. Clair Obscur stands as a prime example of a double-A game, with a larger-than-independent budget, smaller development team, and lower price point on launch.

Budgets for game development are skyrocketing at an exponential rate. When Destiny first launched in 2014, it was called the most-expensive game created yet, totaling to $500 million due to marketing and royalties, but in actuality, likely took $140 million to make, still a sizable chunk. Horizon Forbidden West and The Last of Us Part II, according to court documents, each cost over $200 million. The ever-delayed Star Citizen is reported to have cost around $800 million to develop so far, and a release window hasn’t even been considered yet. Can you imagine? We’re on our way to the first billion-dollar game! Purchasing the games themselves has become more expensive as well, with Ubisoft justifying a $70-price tag for Skull and Bones in 2024 by calling it the first-ever “quadruple-A” game. Now, Nintendo is even joining in, with Switch 2 games costing as much as $80 for physical copies. Publishers and developers defend these costs by touting the amount of playtime and hours of enjoyment their games can provide. You’re just getting every cent worth out of your purchase, in other words, right?

In today’s market, just because you’re spending more does not mean you’re paying for quality. Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League was supposed to be Rocksteady’s next leap forward in the DC Universe. However, grindy gameplay, technical problems, and a dubious narrative led to the developers ending support for their online shooter less than a year after its initial release, putting the future of the franchise at risk. Redfall was such a flop for Arkane Studios that Microsoft decided to close their entire Austin, Texas office. The most infamous example in recent memory, though, has to be Concord. This hero shooter in the vein of Overwatch and Apex Legends spent eight years in development, only to be shut down after just two weeks. What is causing these games to end up so poorly after millions of dollars and years of manpower invested into them?

There are a few reasons why these big-budget games don’t meet the mark. Investors and shareholders for these major companies want to make sure they get a return on their investment, so they often choose to budget games and push for decisions that are “safe” and will be beneficial for their bottom line. Related to that is the inclusion of live service models, which have replaced downloadable content as the primary money-making scheme for publishers. By adding subscriptions and microtransactions in the form of “battle passes,” a game’s lifespan can be elongated and monetized far beyond its initial release. Ultimately, what I think it comes down to is that, for the people making these major financial decisions, fun isn’t what sells. Engagement sells, whether positive or negative. There’s no such thing as “bad press,” in other words. Anything that can bring attention toward their game and possibly bring in even another cent is prioritized. We’ve seen this in other industries, too, where the products are increasing in cost while decreasing in quality. Enshitification has now crept into the game industry. Triple-A games were originally meant to represent a high standard for games, where the investment is proportional to the caliber of the game. It was not meant to be the default state, where millions of dollars can be dropped at a moment’s notice in service of profits down the line.

That is not to say that I hate triple-A gaming. Mass Effect, my all-time favorite, is considered triple-A. Right now, I’m currently making my way through Star Wars Outlaws, another triple-A title. Down the line, games like Ghost of Yotei and Intergalactic: The Heretic Prophet are very intriguing, and I would be interested in getting a Nintendo Switch 2 if and when the console and games become more affordable. But right now, I want to get the most bang for my buck when it comes to games, and we are seeing some excellent properties being released, like Stellar Blade, Lies of P, A Plague Tale, and Robocop: Rogue City. I don’t necessarily care who makes my game, so long as it captivates me.

Former designer on World of Warcraft Chris Kaleiki has stated that there exists an “underserved” market for games that are “more substantial than indie” but aren’t going to “make billions of dollars.” With how well Clair Obscur is currently selling, that statement may need to be revised.