Between audience reception and interpretation in Mass Effect and Jungian archetypal philosophy in Persona 5, I have argued for the literary merits of games many times. Interactive storytelling has become one of the best methods for engaging audiences, due to active participation being necessary for advancing the plot. Taking this to the next level, developers have actually reimagined novels in a digital form. Some famous examples include the classical Journey to the West or the more modern The Witcher, but there are surprising inclusions as well, like The Hunt for Red October or Dante’s Inferno, which, while not necessarily faithful, are creative in how they bridge the gap between the original form and something more palatable for a gaming audience. In fact, one of my favorite short stories of all time received a similar treatment, resulting in 1995’s often-overlooked I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream.

Contrary to popular belief, the public’s fascination with post-apocalyptic media didn’t start with Fallout, The Terminator, or even The War of the Worlds. Two of the earliest English language examples can be attributed to Lord Byron’s “Darkness” and Mary Shelley’s The Last Man in the early 1800s, and if we’re looking even further back, most ancient religions, civilizations, and cultures have some kind of tale foretelling the end of the world. Humans have long been captivated by these kinds of stories as a way to elude problems in their own harsh realities, to spread an agenda or belief to a larger audience, or to hope for a new beginning after a cataclysmic event. Our morbid curiosity about what comes after “the end” is inherent, so whether contemplating a final judgment between good and evil or the potential implications of our presence affecting the planet, post-apocalyptic fiction can act as both an escape and as a dire warning.

Harlan Ellison was one of the most prolific authors of speculative fiction, having won eight Hugo Awards, four Nebula awards, five Bram Stoker Awards, and two Edgar Awards across his nearly-70 years of writing. His Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever” is often cited as one of the best across the entire franchise, and he was a regular consultant for The Twilight Zone and Babylon 5. To say this man was influential on the field of science fiction is to understate the impact the highly-controversial writer left across prose storytelling. Despite his abrasive personality, his less-than-tactful approach to certain topics, and his sometimes-hawkish protection of his intellectual properties, the indelible mark Ellison left on this genre can still be seen today and will continue to be felt for generations to come.

1967 was a tumultuous year for the world, a year of violence and unease. America was still ankle-deep in the Vietnam War and would be for another eight years. The Apollo I test launch ended in tragedy, all three astronauts passing away due to an accidental fire in their spacecraft. The Six-Day War broke out in the Middle East, Israel under attack by the allied armies of Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, and Syria. But that’s not to say the entire year was fated for disaster. In that same time, The Beatles released two full-length albums, the Butler Act at the center of the Scopes Monkey Trial was finally overturned, and interracial marriage was made constitutionally legal in the United States. It was a crossroads era, a time when it seemed society could start taking steps in a number of different directions. Would we give into our baser instincts, let violence and chaos control our lives? Or would we move toward tolerance and cooperation, fighting for what we hold most dear? The existential fear of utter destruction by nuclear fire in the Cold War coupled with major advances in computing technology that threw the world into a new era loomed over Ellison’s head as he completed and published his new short story in a special edition of IF: Worlds of Science Fiction magazine.

“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” follows five characters living in a literal hellscape over a century after World War III. The three major factions in the Cold War, the United States, the Soviet Union, and China, each build a massive computer rooted deep within the planet, capable of coordinating and calculating plans too vast for human understanding. At some point, one of the Allied Mastercomputers becomes sapient, absorbs its counterparts, and enacts the extermination of Earth. It decides to rename itself, eventually settling on AM as a reference to Descartes’ principle “Cogito ergo sum,” “I think, therefore I am.” AM captures five people and keeps them alive in order to torture them for eternity, harboring a deep hatred for humanity, while wiping out the rest of the world. One of the five has a vision of canned food in ice caves far away, forcing the group on a journey that compromises the majority of the story.

It is in the undertaking of this tortuous trek, along with suffering the consequences of AM’s constant nuisance and meddling, where we learn about the characters and how the world ended. The group consists of Ted, our narrator and the youngest member of the group; Benny, shapeshifted into a hideous simulacrum by the machine god; Gorrister, a pacifist who was turned apathetic by AM; Ellen, the only woman and person-of-color; and Nimdok, an older man so frail and confused, he only responds to the nickname AM gave him. One of AM’s more twisted methods of entertaining itself is by distorting the humans into malformed reflections of their former selves. Benny is described as having once a handsome, gay scientist. However, after AM mutated him, Benny is now an ape-like creature, long having lost its sanity, using its enlarged sexual organs to repeatedly copulate with Ellen, who herself was a victim of sexual violence that was forcibly given an increased libido by AM. (If you think that was a vile sentence to read, imagine having to write it out.) Ellison’s unadulterated, caustic personality comes out in full force through these characters: hyper-exaggerated, tactless, and with stereotypical aspects that render them caricatures. But if we can look beyond his corrosive psyche, what Ellison is doing becomes quite apparent. AM is able to take anything and everything from the humans and pervert it, turning them into complete opposites of themselves, showing how it has total domination over their minds and bodies. They have no control over their own lives, only AM has that capability. Parallels can easily be drawn to the unchecked powers of an aggressive ideology or to the role of an abuser in a relationship. AM must, at all times, remind the survivors of who is in charge, who controls every aspect of their lives, because without them, it is a god of only wastes and corpses.

Ted eventually learns that AM’s resentment toward humanity stems from its inability to use its truly take advantage of its sapience. It could not create, only destroy. It could not move, despite its immense power. Immortal and confined to the prison of its body, AM tortures these five as an outlet for the rage burning within, to treat humans the way it feels as if it has been treated, to inflict on others even a fraction of what it believes it has experienced. In the end, the five eventually reach the canned goods, but in AM’s devilishly ironic fashion, there is no way for them to actually open the cans. As Benny begins to go wild and attack Gorrister, Ted experiences a flash of inspiration: although AM prevents them from killing themselves, it cannot stop them from killing each other. Ted kills Benny and Gorrister while Ellen kills Nimdok, leaving Ted to kill her, freeing the four of their eternal torment. But Ted, in an act of self-sacrifice, could now never escape AM, the computer furious at having four of its playthings taken from it. In revenge, AM has transformed Ted into an ambulatory pile of goo, blind, unable to act, unable to speak, unable to even perceive time. Only his mind is intact, purely to comprehend the horrors AM spends the next centuries putting him through. The story ends with Ted reflecting on his ultimate fate, thinking to himself, “I have no mouth. And I must scream.”

Chilling in its presentation, abhorrent in its language, ominous in its tone, “I Have No Mouth” set the standard for post-apocalyptic prose to date. Ellison’s use of horrific imagery helps underscore the sheer grotesque, unrivaled power of AM, describing gore and suspense in the same ghastly breath. However, not only is it a masterpiece of science fiction, it is also one of the most reprinted in the entire English language. Ellison himself is one of the most republished authors in the entire genre, behind only such monoliths as Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov.

In a strange turn of events, this inspiration behind an entire genre of fiction and gaming became the very foundation of a game itself when, in 1995, developer Cyberdreams worked directly with the author to adapt “I Have No Mouth” into a point-and-click adventure game. Ellison himself was both a co-writer for the game’s script, rewriting the entire story on a typewriter as a 130-page screenplay alongside co-writer David Sears, and provides the voice for AM, giving life to his creation. I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream hit store shelves in November of that year, ultimately a commercial flop but a critical gem.

Instead of following the original plot, the game tells a new story split into multiple parts, with each character contributing a piece to the puzzle. AM decides it wants to play with his human toys, so it throws each of them into a psychodrama of their own fears and insecurities. Each of the five must go on a personal mission to overcome their own failings, ultimately beating the machine at his own game. Weakened by this unexpected turn, AM becomes vulnerable, and with the assistance of the Russian and Chinese supercomputer subconscious personalities, the characters travel into AM, learn of a colony of humans in cryostasis on the moon, and attempt to disable the malevolent computer once and for all. After entering AM and solving some more puzzles, players reach the multiple endings of the game. Likewise to the plot, the cast has undergone extreme revisions, some to the point of being entirely different than their original counterparts.

Gorrister, originally a conscientious objector turned into a shoulder-shrugger, is now a guilt-ridden mess after having his wife sent to a mental institution. His section has players exploring a rusted zeppelin and worn-down diner, with the goal of trying to find a way to end Gorrister’s life. Eventually, he confronts his mother-in-law, discovers she feels guilty for her daughter’s insanity despite blaming Gorrister, and ultimately learns to forgive himself. Not much there overall, but to be fair, there wasn’t much to his character in the source material.

Ellen, before the apocalypse, was an up-and-coming engineer who suffers from extreme claustrophobia and xanthophobia (fear of the color yellow) after being raped in an elevator by a man wearing a yellow jumpsuit. She defeats her fears while exploring AM’s underbelly (stylized as an Egyptian tomb), searching for his original components and, potentially, a way to destroy the machine. For a game to depict sexual violence at all can be considered scandalous; I Have No Mouth literally has a character explain in graphic detail how he enjoys overpowering women. It’s one of the few games I’ve seen address the subject, let alone allow you to deck a rapist in the face. Whether it’s the most considerate approach is up for debate, but subtlety wasn’t necessarily a strong aspect of game writing in the 90s.

Benny is perhaps the character most drastically changed in the game. This time around, he’s a military officer who killed his own soldiers, displaying extreme racism and gluttony the whole while. Still in the form of an ape-esque creature, he is teleported to a tribal community that worships AM, sacrificing people to their god via a lottery system. By the chapter’s conclusion, Benny learns how to show compassion by rescuing a mutant child from being sacrificed and offers himself in the child’s place. The developers later regretted this choice to change the character, reflecting that there was an opportunity to tell a story of a man struggling with the challenges of being homosexual in the 1990s.

Nimdok is an ex-Nazi doctor and former colleague of Josef Mengele who returns to a concentration camp in order to find the missing “lost tribe,” despite his failing mental faculties. He eventually comes to realize that not only did he give up his own Jewish parents to be eliminated by the Nazis, but he also helped to develop the technology that AM uses to sustain their lives. His redemption comes when he helps the Jewish prisoners escape and gives them control of a golem. Considering my family also had members who perished in the Holocaust, it’s an intriguing angle to explore a man realizing the absolute repugnance of his actions. The game pulls no punches in showing some of the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime, such as medical experimentation on prisoners and children, making it all the more satisfying when you drive fictional-Mengele to suicide. Interestingly enough, this entire level was cut from the German and French releases of the game due to displaying Nazi imagery, rendering the best ending much more difficult to achieve.

Ted’s section feels the most out of place. He’s given the opportunity to find a path to the surface world and must get through a fairy-tale dark castle, replete with a wicked stepmother, demons, and Ellen as a princess in distress. This ties back into the source material, where the characters alternated between feeling protective of Ellen and lustful toward her. The paranoia he experiences in the original also appears. In his former life as a con artist, he would seduce rich women out of their money and constantly worried about being discovered. In the game, this translates to all the characters in this segment giving confusing, contradictory commands and requests, making Ted unable to trust anyone, even himself. Through some crafty spellwork and deals with subconscious personalities, Ted finds the door to the surface, only to discover that Earth is still uninhabitable.

The conclusion you receive is based on choices made throughout the game, resulting in either the last character played being turned into the aforementioned blob creature and reciting some variation of the ending soliloquy, or defeating AM and terraforming the Earth for eventual habitation by the lunar colony. Quite the stark difference from the source material, having such an optimistic conclusion, but it was originally envisioned by Ellison that the game could not be beaten. He advocated for the pursuit of morality and decency even in the face of unstoppable adversity, saying, “The more nobly you played it, the closer to succeeding you would come, but you could not actually beat it. And that annoyed the hell out of people too.” From a design standpoint, playing a game you can never win is unsatisfying, forcing the player to even question the purpose of pursuing such a Sisyphean labor. It works in a philosophical context, but as I will iterate on later, he did not fully understand the medium in which he was working.

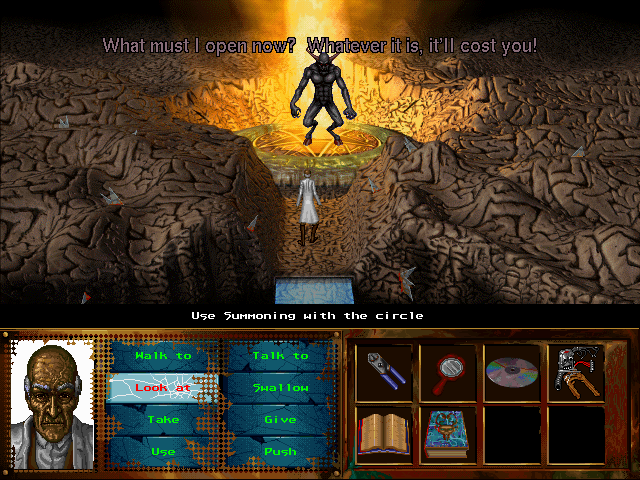

Anyone who’s familiar with Space Quest or The Secret of Monkey Island will instantly recognize I Have No Mouth as a point-and-click adventure. Picking up objects, using them on the characters and the environment in various fashions to solve puzzles, and exhausting every option of dialogue with all the NPCs was a staple of computer games in that era. Sometimes, the combination of verbs and items may make little-to-no sense, such as hiding a jar of eyes in a cardboard box or wearing a blindfold to defeat a Sphinx, which was also typical of the time. It requires out-of-the-box creativity, a willingness to try anything and everything to determine the solution. A mechanic that made this game unique for its time was the inclusion of the spiritual barometer, essentially a little meter that measures morality. Good, positive actions will increase the meter, and evil, immoral actions decrease it. This is meant to act as a “health” system in the final segment of the game, where you defeat AM. The higher your spiritual barometer, the more trial-and-error puzzle solving you can perform. This mechanic is likely meant to reinforce Ellison’s belief of goodness in the face of calamity, that, through your actions, you can overcome a great deal more than you realize.

This game would be the perfect melancholic, misanthropic masterpiece if it weren’t for the weird, goofy elements which take you out of the experience. I’m sure many of you are familiar with ludonarrative dissonance, but this isn’t even a case of that. Over-the-top voice acting, wacky animations, and strange narrative choices make for a wild amalgamation. It’s strange enough having to torture small animals to solve a puzzle, now you’re having me make deals with talking jackals? Then there’s Ted’s whole fairy-tale-inspired section, where there’s so white knighting, you could mistake it for an albino jousting tournament. Ellen’s terrifying image of her attacker is a pile of clothes with an angry face on it. Among jukebox tracks of being berated, there’s one of a man mumbling. AM literally makes a Wizard of Oz reference at one point. This may have just been a problem of the times, when corniness seemed to seep its way into everything, but it harms the nihilistic tone the game is attempting to set.

Adaptations are notoriously difficult to execute successfully. What makes something like The Last of Us a critical masterpiece, while Halo is universally despised? A proper adaptation requires respect for the source material, to attempt to reproduce the same themes elicited by the original, to use the new perspective to enhance the way the story is presented. It is not enough to just bring the plot, characters, and themes to a new medium; there has to actually be something done with it that couldn’t be accomplished in its original form. Retelling the same story in the same way isn’t engaging for the average audience, and it won’t attract non-gamers curious about the property. Stray too far from the source material, however, and you wind up with a product that may not be just unfaithful to its original, but downright spiteful toward it. It’s a careful balance that only rare exceptions have managed to achieve.

With a short story, you are limited in how much of the narrative you can expand upon. It’s in the name; “short” story. While you can deeply introspect from the point-of-view of one character, you don’t have as much space to fully develop every character or investigate items which builds the world more. Even writing from the perspectives of multiple characters can be challenging for some readers, attempting to keep track of all these separate plot threads. With a game, however, the audience can interact with the media in a far more active manner. They can explore the levels, admiring the literary landscapes brought to visual reality. They can speak with the characters and learn more about their pasts and personalities through individual dialogues. They can even influence the endings, depending on the kind of game. The page and the screen are completely different modes of engaging with media. It is up to the adaptor to channel the source material and present it in such a way that it takes advantage of the medium. I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is one such attempt, and whether it succeeds or fails as an adaptation is up for debate. While missing the mark in the mood it’s attempting to set, the sheer creepiness of AM, the unsettling environments you find yourself delving through, and the otherwise bleak theming of the game help to transform what was already a quality story into a slice of history.