Over the last 20 years since I started getting into video games, I’ve probably played well-over 150 separate games, everything from action-packed shooters to choose-your-own-adventures. Every so often, I find myself yearning to play one of these classics again. Modern games have many quality-of-life improvements and many more hours’ worth of content, but there’s a reason that some titles stand the test of time while others are only good for a single playthrough. This is part of a series of entries wherein I talk about games I’ve already played numerous times over the years, but now taking an even closer examination into them. While some of the games I’ve written about before are just as old, it was my first time playing them when I wrote about them. These games, I’ve beaten multiple times and tried to experience everything the game has to offer.

I’ve always had an affinity for Mario’s green-clothed sibling. As the youngest of four in my own family, I naturally assumed the role of the “little brother,” even with three older brothers to bicker among themselves concerning the pecking order. And even when we played Mario Party and the like, I tended to select Luigi as my avatar. Unassuming, not in the spotlight, ready to prove himself, supportive of his family. I believe those describe both myself and the junior plumber quite accurately. Not counting the 1990 LCD watch game Luigi’s Hammer Toss, nor the 1993 officially licensed educational game Mario is Missing!, Luigi has never had his own starring role. (Look at that, the first game in which he’s the main character, and it’s the year I’m born. Yet another connection I just realized while writing this.) Even in Mario is Missing!, his own name is missing from the title! It wouldn’t be until 2001, with the launch of the GameCube, that Luigi finally earned the lead part in a fully-fledged game: Luigi’s Mansion.

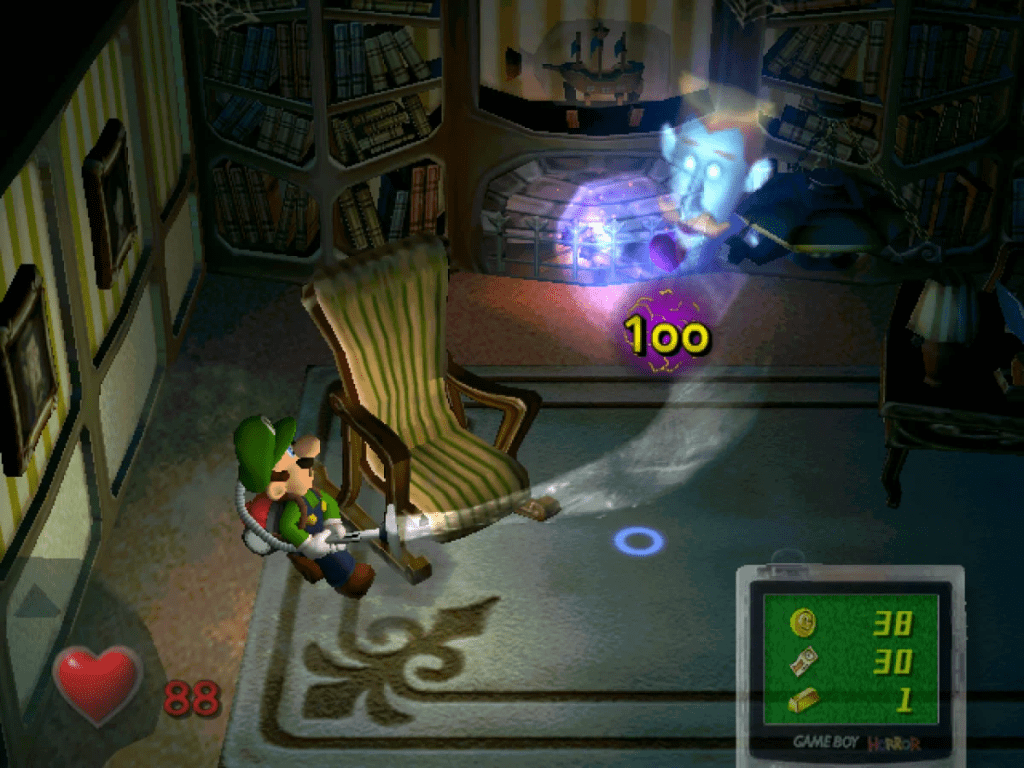

The eponymous character is notified that he has won his own mansion in a contest he never entered, and so he and brother Mario agree to meet up at Luigi’s new digs. Not far inside the sinister and spooky-looking estate, he’s attacked by ghosts and saved by the pint-sized Professor E. Gadd, who tells Luigi he witnessed Mario disappearing into the building along with the spirits he had converted into paintings and which somehow escaped. The mad scientist equips Luigi with the Poltergust 3000 vacuum cleaner and a Game Boy Horror and sends him off into the manor to find his brother and capture the ghosts inside the Poltergust’s containment chamber. Luigi learns that King Boo manifested the mansion in order to catch both him and Mario, and must defeat the inhabitants of the haunted abode in order to reach King Boo and rescue his captured brother.

Nintendo tries to innovate with each new game or console they invest their time in, and Luigi’s Mansion is a true iteration of that philosophy. Unlike previous Mario games in which you might be expected to complete platforming challenges, you stun specters with your flashlight and suck them up with the vacuum, clearing the mansion room-by-room of ethereal villains. The Poltergust can be finnicky to control at times, but once you start to master it, you’ll be taking on entire rooms without much challenge. You’ll even acquire upgrades to the Poltergust that allow you to wield the elements, blowing fire, water, or ice from the vacuum and enabling new methods of taking on what the game puts in front of you, an approach to game design I always appreciate. Occasionally, Luigi will have to face a portrait ghost, a special enemy that requires solving a small puzzle or fulfilling particular conditions in order to capture, breaking up the arcade-like pace of the normal ghosts you encounter and regularly asking you to think outside the box. Each one needs a unique solution in order to defeat, making each memorable in their own ways, apart from their more humanoid forms compared to the majority of other enemies you meet.

As you make your way through the haunted house and capture more ghosts, you can find treasure in the form of coins, bills, bars, pearls, and gemstones, which add to your total score and determines what kind of home you end up with upon the game’s conclusion, whether a meager hovel or an even more mammoth chateau. You can search for stashes or secret chambers throughout the game, finding ways through small holes or hidden entrances, or capturing rare ghosts that occasionally float throughout the mansion. These treasures, while ultimately unnecessary in order to beat the game, provide you with yet another additional measure of how successful you are in exorcising the mansion. That’s one of the many things games can be about, friendly competition, playing against one another, comparing scores and completion times. That kind of spirit can be found in today’s Forntite or Call of Duty, but the original arcade games of the 1970s and 1980s paved the way for competitive gaming to become a mainstay of modern culture.

Your goal is to recapture all of the portrait ghosts, fully unlock the mansion, round up as many Boos as you can find, defeat King Boo, and find your missing brother. Sounds like an overwhelming task, right? Part of the strangely sadistic charm of this game is Luigi’s fearfulness adds to the atmosphere and reflects the state of his current location. Humming along to the main soundtrack of the game, Luigi will chatter when ghosts are nearby in a haunted room, or peacefully whistle when in a lit area. As mentioned, the music of the game is infections. I find myself absentmindedly humming it even today. The ghosts’ designs are colorful and unique, giving them a sense of character that I feel are lacking in the modern designs of more recent entries in the series. The mansion itself is a character, with distinct and themed rooms scattered throughout, including a ballroom, a gymnasium, a pool hall, and even a psychic reading room. One fun recurring trope is the naming convention of the Boos, all puns using the word Boo, like PeekaBoo, Bootique, or even Booigi. These are all part of the comedic charisma Mario games contain, oozing character and style, making them immediately recognizable even when they break the foundations of whatever genre they’re experimenting with.

Having played its sequels, I can certainly say that I enjoy them, too, with their more solid gameplay improvements and the new mechanics and challenges they offer. Maybe it’s just the nostalgia talking, but Dark Moon and Luigi’s Mansion 3 are missing that special something, that rare confluence of elements that makes a game have a lasting impact. I know I’m incredibly harsh on sequels of games or narratives, often arguing they don’t have the same “oomph” that the originals had. I might also be just yearning for new intellectual properties, chasing the next big thing, the next innovative idea, but again, that isn’t to say I don’t like the later entries; you should see the number of hours I invested in Luigi Mansion 3‘s multiplayer. But games like the original Luigi’s Mansion are why I write these articles, why I’ve pursued gaming as both an entertaining hobby and academic field.

Hybrid genres, especially the intersection of horror and comedy, have become ubiquitous in pop culture, attempting to take the best of two separate fields and combine them into something which can elevate the product beyond its base ingredients. I’m not necessarily comparing Shigeru Miyamoto to Oscar Wilde. My point is that, sometimes, taking chances with something different can pay off. If this game came out the same but sans Mario elements, it might have some niche popularity in the same vein as CarnEvil or Illbleed, even being compared to Ghostbusters for their similar ghost-capturing devices, but the Mario charm is what helps to make the game stand out. The care of craft and attention to detail Nintendo is known for show themselves time and time again when they are allowed to try creating something new, and Luigi’s Mansion is a testament to that experimental ingenuity that’s made Nintendo internationally recognizable.